Billy Bunter Goes to Butlin’s: When Boarding School Met the Holiday Camp

- David Salariya

- Jan 17

- 22 min read

How Billy Bunter ended up at Butlin’s reveals a forgotten moment of British marketing genius — a strange collision between boarding-school fantasy, post-war leisure, and children’s publishing in the early 1960s.

The Butlin’s Story

Like most children in Britain in the 1950s and 60s, I was desperate to go to Butlin’s. In my head it was pure Technicolour: Redcoats, blue pools, yellow signage — a future you could queue for. So when I discovered Billy Bunter at Butlin’s (Cassell, 1961), it felt improbable in the best way: Greyfriars decanting itself into Skegness. Latin verbs replaced by knobbly knee contests. The tuck box meeting communal dining and tinned fruit.

What Butlin’s understood — long before anyone talked about “brand ecosystems” — was that the future of marketing lived inside ordinary family rituals. Breakfast mattered. Kellogg’s cereal boxes were handled daily: trusted, argued over, read at the table. By partnering with Kellogg’s, Butlin’s slipped itself effortlessly into domestic life: vouchers inside Corn Flakes, offers promising free or discounted entry, the sense that a holiday had already half-begun before anyone left the house.

The imagery on the back of the cereal boxes did the rest. Children swimming, seen through a glass wall, waving at parents seated in a café — it felt futuristic, utopian, a vision of leisure without barriers at the British seaside. And this is precisely where Billy Bunter at Butlin’s makes sense. Bunter was already embedded in childhood routine through books, radio, and the BBC television series; he was familiar, trusted, part of the furniture. Sending him to Butlin’s was not a novelty stunt but a continuation of the same strategy: meet children where they already are. Just as Kellogg’s reached them at the breakfast table, Bunter reached them in their reading lives.

The result was seamless. Greyfriars didn’t invade Butlin’s; it dissolved into it. Story, brand, and memory aligned so neatly that the marketing barely registered as marketing at all.

And yet — against all odds — it worked.

Spectacularly.

Billy Butlin — Channel 4, 1997

Billy Bunter

The Book That Shouldn’t Exist (But Does)

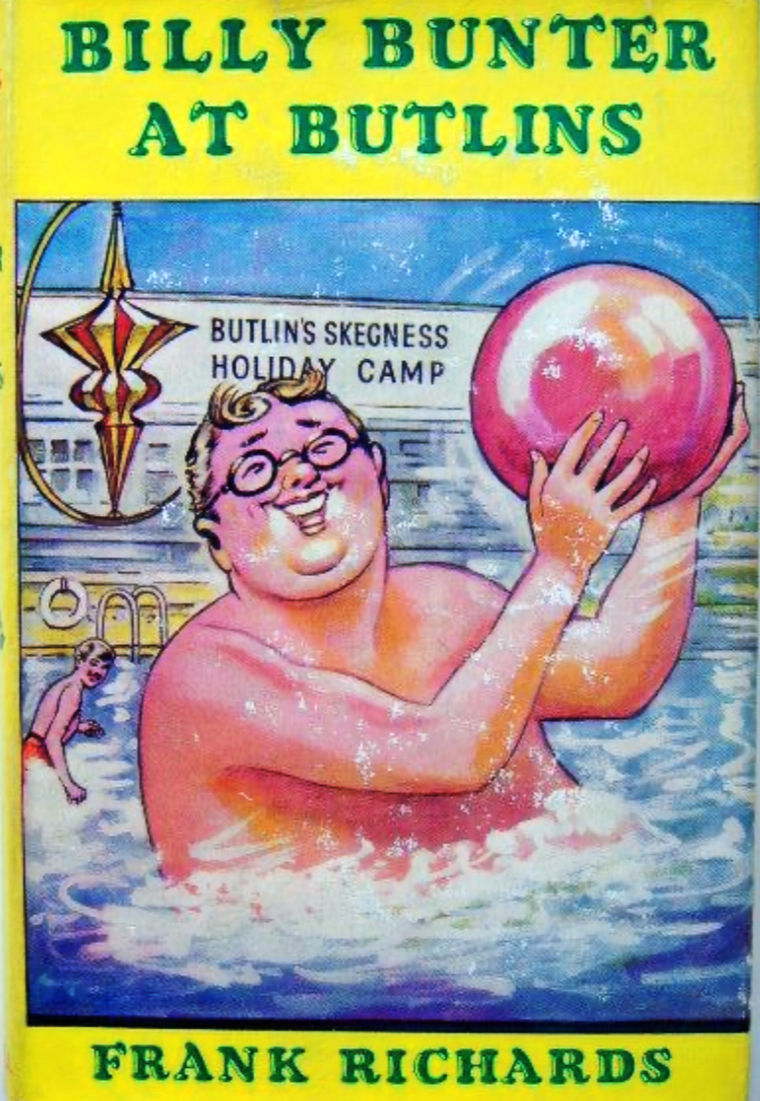

Published in 1961 by Cassell, Billy Bunter at Butlin’s was one of the final novels written by Frank Richards (Charles Hamilton). On the surface, it reads like a novelty: Bunter and his schoolfellows escape the cloisters of Greyfriars and descend upon a modern British holiday camp at the personal invitation of Billy Butlin himself. Throughout the book, Richards describes the then sixty-year-old entrepreneur as “blue-eyed”, “ruddy” and “portly”.

The plot is pure late-period Bunter farce. Bunter expects a dull summer at his uncle’s boarding house washing dishes, only to find himself unexpectedly flush with cash (acquired in typically dubious fashion) and bound for a free holiday at Butlin’s. There is a colossal amount of sticky eating. There are misunderstandings.

There is a criminal subplot involving a stolen wallet.

There is, above all, food.

But beneath the slapstick lies something far more interesting.

This was not just a story. It was a commercial crossover, a branding experiment, and a quietly radical moment in British children’s culture.

Greyfriars Meets the Masses

Billy Bunter was born into a world of privilege — albeit a satirised one. Greyfriars School, for all its comic cruelty, was an unmistakably public-school environment: hierarchies, fagging, classical education, prefects, Latin, and rigid class assumptions.

Butlin’s, by contrast, was post-war Britain’s great leveller.

Founded on the promise of affordable pleasure, Butlin’s holiday camps welcomed families who had never previously had access to leisure on this scale: communal fun, equal cabins, mass entertainment — a democratic vision of joy.

Putting Billy Bunter into Butlin’s was therefore not just odd. It was symbolic.

It marked the moment when British children’s culture stopped belonging to one class and started belonging to everyone.

The Beaver Club

Childhood as Brand Loyalty

At the heart of this crossover sat the Butlin’s Beaver Club — one of the most effective children’s clubs ever created in Britain.

Founded in 1951, the Beaver Club was free to join and offered:

a metal and cloth badge

a personalised membership card

birthday and Christmas cards posted to children at home

radio shows

dedicated Beaver Club lodges at camps

annual reunions at the Royal Albert Hall

Children didn’t just visit Butlin’s. They belonged to it.

Billy Bunter at Butlin’s was published specifically for this audience. Copies carried a special Beaver Club dust jacket featuring a photographic image of Gerald Campion, the actor who played Bunter in the BBC television series. The usual artist, C. H. Chapman, did a cover as well.

This was 1961 — and this was brand immersion.

The BBC, Gerald Campion, and the Face of Bunter

By the early 1960s, Billy Bunter was no longer simply a character from a book. Thanks to the BBC television series Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School (1953–61), he had a face.

That face belonged to Gerald Campion.

Campion’s portrayal fixed Bunter in the public imagination: wheezing, sly, infantile, an irresistible glutton. Using his image on the book’s cover was a masterstroke. Children recognised him instantly. The BBC wasn’t officially promoting Butlin’s — but its cultural capital was being quietly borrowed.

No fuss. No scandal. Just a seamless glide between media, publishing, and leisure.

Was Anyone Cross?

Surprisingly, no.

There’s little evidence of contemporary criticism. Parents didn’t protest. Reviewers didn’t panic, not many books for children were reviewed back then. Children simply enjoyed the story — and many received the book as a prize or souvenir from their holiday.

If anything, the public response suggests recognition of something rather modern: that pleasure, literacy, and commerce could coexist. The book likely sold in quantity; original editions remain fairly easy to find.

This wasn’t exploitation. It was participation.

Why It Matters Now

Today, children’s publishing frets endlessly about discoverability, engagement, and relevance. In 1961, Butlin’s quietly solved the problem.

They understood:

children like belonging

stories extend experiences

characters build trust

memory is a marketing tool\

Billy Bunter at Butlin’s is not an embarrassment. It is a case study — a reminder that British children’s culture once knew how to be playful, confident, and generous, without anxiety or apology.

I suspect Billy Bunter himself understood the arrangement perfectly.

He ate. He holidayed. He was remembered.

Which, in the end, is more than can be said for many a modern corporate initiative dressed up as a reading campaign.

Today we talk about “discoverability” as if children are empty search engines waiting to be optimised. But Butlin’s understood that stories don’t need to be pushed — they need to be woven into lived experience. Bunter didn’t advertise Butlin’s. He belonged there. And that difference — between interruption and integration — is where much contemporary children’s publishing quietly loses the plot.

Billy Bunter’s Hunger

A Post-Rationing Appetite

Reading Billy Bunter at Butlin’s today, what strikes most forcefully is not the holiday setting — indeed, the camp itself remains oddly indistinct — but the book’s relentless preoccupation with hunger. Billy Bunter eats constantly: furtively, guiltily, and without satisfaction. What is often dismissed as crude comic excess begins to look different when read through the lens of post-war Britain.

Food rationing officially ended in 1954; sugar and sweets a year earlier. But emotional habits do not obey ministerial announcements. For those who lived through wartime scarcity — and for children raised in its long shadow — food remained charged with anxiety, desire, and mistrust. Frank Richards did not need to explain this. His readers understood it instinctively. Bunter’s greed is not rooted in abundance but in fear: the fear that food might vanish, that pleasure must be seized quickly and secretly before it is taken away.

Notably, Bunter is rarely shown eating communally. The Butlin’s dining hall — supervised, orderly, reassuring — is narratively sidelined. Instead, he consumes sticky buns, jam tarts, toffee, sandwiches: illicit foods associated with consolation and reward. These are not the foods of plenty; they are the foods of relief. He eats alone, in corners, leaving crumbs behind him. Satisfaction is always provisional. The next hunger is already arriving.

Seen this way, Bunter is temporally displaced — a wartime appetite wandering into a post-war world that insists the cupboards are now full. His excess feels embarrassing, even grotesque, because society has moved on while he has not. The joke works because it is uncomfortable. He embodies the lingering mistrust of comfort itself.

Read now, Billy Bunter’s hunger can feel ugly. But it is also historical. His greed is a ghost of rationing — proof that scarcity leaves marks long after it ends.

The Menace Under the Chalet Door

One of the creepiest elements in Billy Bunter at Butlin’s is the way real criminal menace slips into what is meant to be a safe, regulated holiday space. The "weasle eyed' pickpocket does not just follow Bunter to Butlin’s; he enters Bunter’s chalet at night, moving about the bedroom with a torch while Bunter sleeps.

The scene is witnessed not by an authority figure, but by Horace Coker, who has come for an entirely different purpose — to give Bunter a beating. The collision of threats is startling: juvenile bullying meets adult crime in the most intimate possible setting, the sleeping body. Richards plays it for tension, but the unease lingers.

The holiday camp, marketed as abundance and safety, proves permeable. Locks fail. Supervision evaporates. The boundary between childish punishment and genuine danger collapses. It is a moment where the book briefly stops being comic and reveals something darker: that post-war fantasies of security are fragile, and that Bunter — greedy, ridiculous, and helpless — is far less protected than the world insists he should be.

Why “Fixing” Billy Bunter Didn’t Work

By the 1980s, Billy Bunter had become a relic from another age. Created in 1908, he had survived two world wars, rationing, television, and the slow collapse of the boarding-school story. What he could not survive was improvement.

In 1983, six Billy Bunter novels were substantially rewritten for modern children by Kay King and published by Quiller Press, with the approval of Richards’s literary executor. The stated aim was to make Bunter acceptable. Out went shillings and pence, Latin tags, Shakespearean references...even a reference to the medieval idea of 'Muhammad's coffin'. But once the blade was taken to the text, it did not stop there. Language was simplified, books shortened, violence softened, class tensions flattened. Corporal punishment was discreetly relocated offstage.

Most strikingly, the language around Bunter himself was thinned. In one original novel, the word fat appeared over 300 times; in the rewritten version it was cut by more than half. The intention was kindness. The effect was neutering.

Because Bunter’s fatness is not a casual insult; it is the engine of the character. His body is metaphor — appetite, excess, fear of lack made flesh. Remove the insistence and the joke collapses. A slimmed-down Bunter is not a better Bunter; he is barely Bunter at all.

The same process dulled everything else. Hurree Jamset Ram Singh lost his idiosyncratic speech; class satire was dampened; servants were sanitised. The books became less abrasive, less cruel — and far less alive.

Commercially, the rewrites failed. Bunter’s late survival depended on nostalgic adults, not new child readers. Those adults did not want a corrected Bunter, and new readers did not arrive to replace them. The rewrites quietly died. Bunter slipped out of print.

Bunter did not die because he was offensive. He died because he was over-corrected.

How Charles Hamilton Got Billy Bunter Back

Billy Bunter was never “owned” by Charles Hamilton in the modern sense. He was created as work-for-hire for The Magnet, published by the Amalgamated Press. When the paper closed in 1940, the publisher retained control of the comic-strip Bunter, redeploying him in titles such as Knockout and Valiant in increasingly broad, slapstick form.

What Amalgamated Press did not automatically control were stand-alone prose novels.

Hamilton noticed the gap.

In 1948, he began publishing new Billy Bunter novels with Cassell, starting with Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School. These were not serials, not tied to The Magnet, and not under Amalgamated Press contracts. Cassell took the risk. The publishers did not litigate.

For more than a decade, Britain had two Billy Bunters running in parallel: a corporate comic asset, increasingly visual and exaggerated; and a prose Bunter, written solely by Hamilton — verbal, school-based, and recognisably his.

The Bunter remembered from books and television owes far more to this reclaimed prose version than to the comics. When the BBC adapted Bunter in the 1950s, it drew on the Cassell novels, not the strip.

Hamilton did not win Bunter back through ownership. He outlasted the system.

Which is why today’s dilemma over Billy Bunter is not really about political correctness. It is about what happens when a character survives its creator as a corporate residue — long after the emotional weather that made it intelligible has passed.

Billy Bunter in India

A Return, Not a Revival

It’s almost certainly no coincidence that Billy Bunter has reappeared in India just as the copyright clock expired. Under Indian law, literary works are protected for the life of the author plus sixty years; Charles Hamilton died in 1961, which means his Billy Bunter texts entered the public domain in India on 1 January 2022. From that moment, the books became legally free to reprint — no licences, no royalties, no negotiations.

Hachette India’s programme is therefore less a revival than a recalibration: the texts can now be handled as artefacts rather than obligations, framed explicitly as adult nostalgia and quietly monetised at arm’s length. This is not about rediscovering relevance, nor about introducing Bunter to new readers. It is about jurisdiction. Billy Bunter has not returned because the times demanded him, but because the law finally allowed it.

This does not mean the books are public domain in the UK or EU yet. There, Hamilton’s work remains protected until 1 January 2032 (life + 70).

Billy Bunter has not so much stormed back into India as been carefully reintroduced. In recent years, Hachette India has reissued a substantial run of Bunter titles — Billy Bunter’s Beanfeast, Billy Bunter’s Barring Out, Billy Bunter at Butlin’s, and the inevitably intriguing Billy Bunter in India — handsomely produced hardbacks with fresh ISBNs for the local market. Some have sold through and been restocked, suggesting interest, though not hysteria.

Crucially, this is not a children’s revival. Hachette India has been explicit that these editions are aimed at older readers — largely those who remember The Magnet or the BBC television series and are now reacquainting themselves with a long-absent companion. Reader responses bear this out. Reviews speak less of discovery than reunion: readers pleased to “finally find Billy Bunter again”, admiring the bindings, relishing the return of Greyfriars after decades.

In this sense, the Indian reissues echo the logic of Billy Bunter at Butlin’s itself. That book was never really about introducing Bunter to a new generation, but about reframing a familiar figure for a changing world, relying on the affection of those who already knew him. Then, as now, the strategy was not renewal but recognition. What is being sold is not relevance but memory.

When an Author Dies: What Enters the Public Domain Next (2026–2031)

Rule of thumb: in most places, copyright expires on 1 January after the term ends — so it arrives as a neat New Year’s Day “handover”.

India: Life + 60 years (works by authors who died…)

Public domain on 1 January of the year shown

2026 (d. 1965): T. S. Eliot, W. Somerset Maugham, Winston Churchill - big history - suddenly cheap to reprint in India.

2027 (d. 1966): Evelyn Waugh, C. S. Forester (Hornblower), Margery Allingham, Flann O’Brien Satire, naval adventure, classic crime, and oddball modernism open up.

2028 (d. 1967): Arthur Ransome (Swallows and Amazons), Siegfried Sassoon, Dorothy Parker, Carson McCullers, John MasefieldChildren’s adventure, WWI poetry, and major American voices.

2029 (d. 1968): Enid Blyton, John Steinbeck, Mervyn Peake (Gormenghast), Upton Sinclair, Helen KellerThis is the blockbuster year - especially Blyton.

2030 (d. 1969): Richmal Crompton (Just William), John Wyndham (Triffids), Jack Kerouac Classic British childhood mischief + British sci-fi + Beat literature.

2031 (d. 1970): E. M. Forster, Bertrand Russell, Erle Stanley Gardner (Perry Mason), John Dos PassosMajor “serious” literature and big-quantity popular fiction become free in India.

The key twist: these authors are still in copyright in the UK/EU for roughly another decade in many cases - so India gets a long head start.

UK & Europe: Life + 70 years (works by authors who died…)

Public domain on 1 January of the year shown

2026 (d. 1955): Dale Carnegie (How to Win Friends…), Wallace Stevens Self-help and modernist poetry become reprintable by anyone.

2027 (d. 1956): A. A. Milne (Winnie-the-Pooh text) BUT: E. H. Shepard’s illustrations are not free until 2047.So: Pooh’s words are free; the “real” drawings still aren’t.

2028 (d. 1957): Dorothy L. Sayers (Lord Peter Wimsey), Laura Ingalls Wilder (Little House) Crime and children’s classics suddenly become open season.

2029 (d. 1958): Geoffrey Willans (Molesworth text)BUT: Ronald Searle’s illustrations remain locked until the 2080s (he died 2011).Same pattern as Pooh: text freed; iconic art still fenced.

2030 (d. 1959): Raymond Chandler (Philip Marlowe)Noir becomes public property - expect a wave of new editions and adaptations.

2031 (d. 1960): Nevil Shute (On the Beach), Richard Wright, Zora Neale HurstonPopular fiction + major American literature re-enters the commons.

The Three Things People Miss

Illustrations can outlive the text.If the illustrator died later, their drawings stay locked longer (Pooh is the classic example).

Translations have their own copyright. Even if the original author is public domain, a famous translation may still be protected if the translator died later — which is why “new translations” often appear right when the original text becomes free

Trademarks can still bite. A story may be public domain, but brand elements (logos, distinctive commercial imagery, sometimes even a character as marketed) can still be protected via trademark.

A note for those reaching for the scanner: the phrase “public domain” is less a destination than a condition, and one rarely achieved all at once. Texts may be free while illustrations are not; translations may remain fenced long after the original has wandered off; characters may escape copyright only to collide with trademark. Anyone contemplating republication is strongly advised to consult a copyright lawyer before proceeding. Calendars have a habit of being clear; copyright law does not.

Closing: Badges, Guitars, and a Free Meal

Billy Bunter at Butlin’s stands at a crossroads. It belongs to post-war Britain of queues, badges, shared tables, and managed entertainment — yet it arrives just as the country is learning to loosen its tie. Greyfriars drifts into Butlin’s at the precise moment when childhood itself is about to change: when organised fun gives way to pop, performance, and the discovery that young voices might be worth hearing.

That Ringo Starr once wore a Redcoat blazer feels less like irony than gentle foreshadowing. Butlin’s taught a generation how to stand up, join in, and have communal fun; the 1960s simply handed them guitars instead of badges. Bunter, eating anxiously in the corner, is already fading.

If there is a lesson here, it is that books outlive power in unexpected ways. And yet a fat boy with a perpetual appetite still finds himself unpacked, once more, in a place he never expected to be — in India. The texts are framed as artefacts, sold, they say, to adults who already know what they are buying, their rough edges neutralised not by editing but by historical distance. Empire has vanished; offence has presumably expired? Bunter survives not because he matters again, but because he is cheap, familiar, and safely past his capacity to cause trouble.

Even Billy himself would understand the arrangement perfectly.

He always did have a keen nose for a free meal.

Key Characters of the Billy Bunter Books

Billy Bunter

Known as “The Owl of the Remove”, Billy Bunter is the centre of Greyfriars. Fat, greedy, cowardly, and endlessly waiting on a 'postal order', he is less a hero than a comic stress-test for the system around him. His appetite—physical and moral—is bottomless, and his refusal to learn is the point. Bunter absorbs punishment, humiliation, and failure without reform. He survives because he endures. In him, excess becomes metaphor: for fear of scarcity, for selfishness, and for the grotesque underside of privilege.

Harry Wharton

The moral centre of the Remove and its nominal leader. Athletic, fair-minded, and conventionally heroic, Wharton embodies the ideal public-school boy. His primary narrative function is contrast: against Bunter’s appetite and evasion, Wharton’s restraint and honour appear luminous—but also a bit bland.

Bob Cherry

Cheerful, loyal, and warm-hearted, Bob Cherry acts as the emotional glue of the Famous Five. He is indulgent toward Bunter, often forgiving him long after forgiveness has ceased to be rational. Cherry represents kindness without authority—an essential counterweight to Greyfriars’ harsher forces.

Frank Nugent

More thoughtful and sceptical than his peer group, Nugent provides quiet intelligence and moral ballast. He is less impulsive than Wharton and less sentimental than Cherry, often articulating what the reader is thinking when Bunter’s antics tip from amusing to intolerable.

Johnny Bull

Bluff, patriotic, and physically imposing, Johnny Bull is the group’s embodiment of muscular Englishness. He acts decisively, occasionally violently, and is most at ease when problems can be solved with fists. He represents the sanctioned force of the school when rules fail.

Hurree Jamset Ram Singh

An Indian prince educated at Greyfriars, Hurree Jamset Ram Singh (Inky) is among the cleverest and most ethically grounded characters in the series. Fluent in deception when necessary and loyal to the Famous Five, he often outwits both bullies and masters. Though written through the imperialistic lens of his time, Hurree frequently exposes the hypocrisy and limitations of the English boys around him.

Horace Coker

A Fifth Former and persistent thug of a bully, Coker is loud, stupid, and violent, using intimidation rather than intelligence to assert power. His clashes with Bunter are especially revealing: brute force meeting comic cowardice, neither admirable, both destructive. Coker represents authority stripped of legitimacy.

Mr Quelch

The archetypal disciplinarian master. Stern, punitive, and implacable, Quelch is the human face of institutional authority. His cane enforces order but never understanding. He exists to maintain the system, not to nurture those within it.

Mr Prout

The benevolent but distant headmaster. Prout presides rather than intervenes, symbolising the upper reaches of authority—reasonable in theory, remote in practice. His absence from daily cruelty is as telling as Quelch’s presence.

characters, plus Bunter’s family, keeping the same pen-portrait style and the sense that these figures exist to apply pressure to the system, not to soften it. I’ve avoided repetition and stayed brisk.

The Wider Bunter World

Mr Bunter Senior

Billy Bunter’s father is a respectable stockbroker, permanently exasperated and emotionally distant. He represents middle-class propriety colliding with an uncontrollable appetite. His punishments are financial—cut allowances, threats of discipline—but he is consistently outmanoeuvred. He exists to demonstrate that even adult authority fails when confronted with Bunter’s persistence.

Bessie Bunter

Bunter’s younger sister, sharp-tongued, observant, and notably unsentimental. Bessie is one of the few characters who sees Billy clearly and takes active pleasure in puncturing his self-importance. Where others are worn down by him, she remains resistant. She is not kinder than Billy—just more competent.

Mrs Bunter

A curiously shadowy presence. Mrs Bunter only appears intermittently, generally indulgent, often flustered, and quietly defeated by her son’s gluttony. She is less a character than an atmosphere: maternal tolerance stretched thin, emblematic of domestic authority that has learned not to fight battles she cannot win.

Uncle Bunter

Proprietor of a seaside guesthouse, Uncle Bunter represents the precarious lower-middle-class economy of boarding houses and seasonal trade. Billy’s visits are invariably disastrous—food vanishes, reputations suffer, bills mount. The guesthouse episodes mirror Butlin’s in miniature: communal eating, thin margins, and Bunter as a one-boy economic catastrophe.

School Figures Beyond the Famous Five

Vernon-Smith

Smarter and more malicious than Coker, Vernon-Smith is the sadist of Greyfriars—cold, strategic, and inventive in cruelty. Where Coker blunders, Vernon-Smith calculates. His presence shifts the tone from rough bullying to psychological menace.

Skinner

Lean, sneering, and permanently contemptuous, Skinner acts as Vernon-Smith’s lieutenant. He is cruelty reduced to reflex—resentful, opportunistic, and eager to exploit weakness, particularly Bunter’s.

Peter Todd

Small, nervous, and perpetually anxious, Peter Todd is Bunter’s moral mirror. Where Bunter externalises fear through greed, Todd internalises it through terror. His presence reminds the reader that not all vulnerability becomes comic.

Fisher T. Fish

An American student whose exaggerated slang and confidence provide cultural contrast. Fisher T. Fish introduces an outsider’s bravado into Greyfriars, unsettling its rituals while reinforcing them through parody.

Criminal & Adult Intrusions

the pickpocket

Appearing most memorably in Billy Bunter at Butlin’s, the pickpocket is a rare instance of real adult criminality entering the schoolboy world. His presence collapses the usual boundaries between comic mischief and genuine danger, exposing the fragility of assumed safety once institutional supervision falls away.

Titles and Hierarchy at Greyfriars School

Forms (Year Groups)

Greyfriars is divided into forms rather than years. The hierarchy matters.

The Remove (Lower Fourth ) Billy Bunter’s form. Roughly equivalent to boys aged 14–15. Old enough to be held responsible, young enough to be bullied with impunity. The Remove is the emotional engine of the series.

The Fifth Form Older, stronger, and socially dominant. Fifth Formers often act as bullies or informal enforcers. Horace Coker belongs here. They exist to remind the Remove where power really sits.

The Sixth FormThe elite. Senior boys who have passed through the system and now enforce it. Rarely comic. They are the school’s internal police force.

Prefects

School PrefectsSelected from the Sixth Form. Prefects have the right to punish younger boys, including administering beatings. They represent delegated authority—cruelty rendered legitimate by structure. Prefects are often more feared than masters.

Form PrefectsSenior boys assigned to oversee specific forms. Their power is local but constant. Abuse of authority is common and rarely punished.

Head Boy

Head Boy (Harry Wharton) Leader of the school—or at least of the Remove. Expected to embody fairness, restraint, and moral authority. The Head Boy exists to demonstrate how the system should work, even as it repeatedly fails around him.

The Famous Five

An informal title, but an important one.Harry Wharton, Bob Cherry, Frank Nugent, Johnny Bull, and Hurree Jamset Ram Singh form the moral nucleus of the Remove. They are not powerful because of rank, but because of loyalty and cohesion. Their authority is emotional, not institutional.

Fags

Fag A younger boy assigned to perform chores for an older one. Fagging is accepted, ritualised exploitation. It teaches obedience early and normalises inequality. Billy Bunter is a spectacularly bad fag.

Monitors & Officials

Dormitory Monitors / Games Captains

Minor offices with limited authority. These roles create the illusion of participation while reinforcing hierarchy. They are often stepping stones to prefectship.

Frank Richards (Charles Hamilton)

Frank Richards was the principal pen name of Charles Hamilton (1876–1961), one of the most prolific writers in the history of publishing. Over a career spanning more than sixty years, Hamilton is estimated to have written well over 100 million words, publishing continuously in story papers, magazines, and books. He wrote under dozens of pseudonyms — Frank Richards, Martin Clifford, Owen Conquest, Ralph Redway among them — often producing multiple serials simultaneously, sometimes for competing publishers.

His most famous creation, Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School, became a defining figure in British children’s fiction. The sheer scale and consistency of Hamilton’s output was so extraordinary that it reportedly earned him a place in the Guinness Book of Records for literary productivity. His anonymity was so complete that George Orwell, writing critically about boarding school stories in boys’ weeklies, assumed Frank Richards and “Martin Clifford” were two separate authors — unaware they were the same man. Hamilton revealed his true identity only late in life, by which time he had quietly shaped half a century of British childhood reading from behind a wall of names.

Gerald Campion

Gerald Campion (1922–2002) was an English actor whose name became inseparably linked with one of the most recognisable characters in British children’s books and TV: Billy Bunter. Though trained as a stage and radio actor, Campion achieved lasting fame through the BBC television series Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School (1953–1961), in which he portrayed the gluttonous, wheezing schoolboy with such conviction that he effectively fixed Bunter’s image for a generation.

Already in his early thirties when cast, Campion’s physicality, comic timing, and vocal mannerisms made the character instantly iconic — but also fatally inescapable. Like many actors who embody a national archetype too successfully, he found himself permanently typecast, his wider talents eclipsed by a single role. Despite appearances in theatre, radio comedy, and later television work, Campion never entirely escaped Bunter’s shadow. His career stands as a reminder of mid-century British television’s power to create cultural immortality — and the quiet personal cost that often accompanied it.

Sir Billy Butlin

Billy Butlin (1899–1980) was a British entrepreneur who more than any other individual reshaped the idea of leisure for ordinary people in post-war Britain. The son of a fairground family, Butlin understood crowds, spectacle, and above all the emotional mechanics of pleasure. In 1936, he opened his first holiday camp at Skegness, founded on a radical promise for its time: a week’s holiday with food, accommodation, and entertainment included, at a price working families could afford. His famous reassurance — “Our true intent is all for your delight” — was not marketing whimsy but a business philosophy.

After the Second World War, Butlin’s holiday camps became a cornerstone of Britain’s emerging mass leisure culture. With foreign travel beyond the reach of most families, Butlin’s offered something unprecedented: structured fun, communal experience, and a carefully engineered sense of belonging. Camps at Skegness, Pwllheli, Filey, Ayr, and Minehead were designed as self-contained worlds, complete with chalets, swimming pools, ballrooms, cinemas, children’s clubs, and the instantly recognisable Redcoats, whose job was to eliminate awkwardness and ensure participation. Butlin’s holidays were not about escape so much as reassurance: predictable, sociable, and democratic.

Everyone queued together.

Everyone joined in.

Crucially, Butlin understood children as central to the holiday experience, not an afterthought. Initiatives such as the Butlin’s Beaver Club extended the holiday beyond the summer week, maintaining year-round contact through badges, cards, radio programmes, and reunions. In this context, cultural tie-ins such as Billy Bunter at Butlin’s were not novelties but logical extensions of a wider strategy: embedding Butlin’s into the fabric of childhood memory itself.

By the late 1960s and 1970s, however, the world Butlin had built began to change. Cheap foreign package holidays, shifting social aspirations, and the decline of communal leisure gradually eroded the centrality of the holiday camp. What had once felt modern began to feel regimented; what had been inclusive was recast as quaintly comic. This transition was sealed in the public imagination by the BBC sitcom Hi-de-Hi! (1980–1988), set in a fictional holiday camp and drawing affectionate humour from the rituals, hierarchies, and forced jollity of camp life. While celebratory in tone, Hi-de-Hi! gently repositioned Butlin’s as nostalgia — something warmly remembered rather than urgently desired.

Yet that retrospective irony should not obscure the scale of Butlin’s achievement. At its peak, the holiday camp was not kitsch but visionary: a carefully designed answer to the needs of a newly democratic society learning how to rest, play, and belong together. Billy Butlin did not simply sell holidays. He sold confidence, predictability, and the radical idea that pleasure itself could be organised — for everyone.

C. H. Chapman (Chappie)

C. H. Chapman (1879–1972), universally known as Chappie, was the definitive visual architect of Billy Bunter. Over decades, his illustrations for The Magnet story paper and later book editions fixed the appearance, posture, and physical comedy of Greyfriars in the public imagination. Chapman’s Bunter — round, perspiring, bespectacled, and perpetually off-balance — was not merely fat, but expressive: greed, fear, bravado, and self-pity all registered instantly in line and gesture.

His genius lay in making cruelty readable without making it monstrous. Prefects loom, punishments land, humiliations unfold, yet the drawings retain a curious warmth that keeps the comedy afloat. Chapman’s work was so closely aligned with Charles Hamilton’s writing that text and image became inseparable; for many readers, this was Billy Bunter. Later illustrators would draw him, but Chapman invented him visually — and his shadow stretches across every subsequent depiction.

R. J. MacDonald

R. J. MacDonald was one of the principal illustrators of the later Billy Bunter novels, contributing artwork to titles such as Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School and Billy Bunter in Brazil. Working primarily in the post-war hardback era, MacDonald brought a slightly cleaner, more formal visual language to the series, often supplying colour frontispieces that framed Bunter as a figure of adventure as much as farce.

His illustrations reflect a shift in context: Bunter removed from the claustrophobic routines of Greyfriars and placed into wider, sometimes exotic settings, where humour coexists with mild peril. While MacDonald’s Bunter lacks the visceral grotesquerie of Chapman’s, his work plays an important transitional role — smoothing the character’s passage from story-paper origins into bookshop respectability. If Chapman defined Bunter’s body, MacDonald helped sustain his late-career survival, adapting the visual tone to a readership increasingly distant from Edwardian schoolrooms.

About the Author

David Salariya is a writer, illustrator, designer, and publisher who has spent a lifetime thinking about how children encounter stories. Despite growing up in the era when Butlin’s loomed large in the national imagination, he sadly never made it to Butlin’s — and, more tellingly, never secured an interview when he applied to become a Redcoat at Butlin’s in Ayr. Instead, his summer job took a more prosaic turn: a stint at Findus, maker of the nation’s most famous frozen fish fingers.

He went on to found The Salariya Book Company and create some of Britain’s best-known children’s non-fiction series, published worldwide. He remains fascinated by the gap between cultural mythology and lived experience — and by the strange routes through which stories, brands, and childhoods actually meet.

Comments