Seven Plots, One Boarding School Universe

- David Salariya

- Aug 4

- 9 min read

Updated: Oct 5

A school friend's family had a contraption that looked like something straight out of Dan Dare, a kind of squashed fishbowl or jellyfish that hung in front of their TV. It was made of a hardish, clear-ish plastic, vaguely domed, and filled with liquid in an attempt to make the picture look bigger, like the technology in Dan Dare,* space gadgets promised sleek solutions, this enlarger was a hopeful (if imperfect) leap into the future of television. Of course, it didn’t really work, all it did was magnify the blur and flicker. But we still stared through it, peering into a world of cathode silver, the glowing white-hot centre of the screen at startup slowly drifting into a phosphorescent bloom, flickering. Beyond that flickering glow, into the real 1950s Britain, a country still hungover from war, rationing, smelling of damp coats and stewed tea, where colour hadn’t so much drained away as simply never returned. It was a world not monochrome but monotonochrome, living somewhere between pea souper fog and institutional linoleum on the greyscale.

This was a Britain seen not in full black or white, but in the lingering greys of endurance. No wonder the glow of a TV screen, the smoke greys, the faint blue cast from the glass, was exciting. The TV wasn't only escapism; it was a form of colour in black and white seeping into our life, promising that somewhere else, maybe just over the horizon things weren’t going to be quite so drab.

So it was through this slightly squashed goldfish bowl I first saw Billy Bunter, and that’s how school stories looked, too, a bit fuzzy, a sort of pantomime, endlessly waiting for something to arrive, recognition, reward, jam, it was always jam tomorrow in the 1950's..

Even in their grainy absurdity, these school stories held us. Billy Bunter, grotesque and greedy, wasn’t just a figure of fun, he was a warning. A comic echo of the schoolboy, unchecked and always in trouble, like the plastic screen, we kept gazing, hoping to see something larger, clearer, more profound just less distortion.

So here was the fat Billy, pompous, thinking that six sausage rolls and a merengue made for a good lunch - food now only served at funeral teas. A kind of tragicomedic Falstaff for the Beano and Ladybird book generation.

Bunter: Larger Than Life

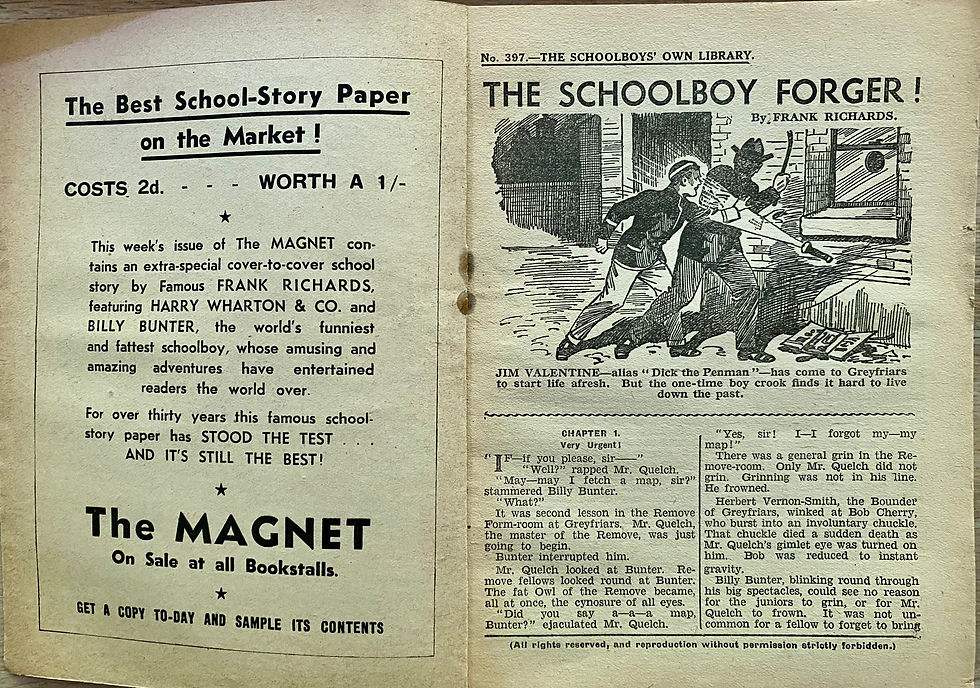

The program was on BBC Television from 1952 to 1961 and was based on what were called 'weeklies', these were forerunners of paperbacks and were sold in pokey, dark little shops everywhere from the 1900's onwards. The Magnet’s Greyfriars stories by Charles Hamilton (a.k.a. Frank Richards) had started in 1908. Bunter was played by 29-year-old Gerald Campion, padded to match the famously rotund schoolboy’s 14-stone reputation. Around him orbited a cast of boys destined for greater fame: Michael Crawford, Anthony Valentine, Melvyn Hayes, Jeremy Bulloch.

It wasn’t exactly high drama. It was similar to my first experience of going to the theatre - panto at Christmas. The dialogue was stiff, the sets wobbly, the performances full of catchphrases. It worked. It felt important. Bunter waiting endlessly for a postal order that never came became a kind of national metaphor for postwar British childhood.

And that Standlens? It turned the show into something mythic. A small moral universe, distorted and magnified, beamed into a child’s imagination.

Bunter, like every school story from Tom Brown to Malory Towers, was playing a part in one of just seven plots. That’s it. According to the late journalist and author Christopher Booker, plots only has seven stories. That’s right, just seven. And every school story you’ve ever read is basically in fancy dress as one (or several) of them.

Let's ring the bell and see what’s on the lesson plan.

Overcoming the Monster

Rags to Riches

The Quest

Voyage and Return

Comedy

Tragedy

Rebirth

And school stories? They’ve done them all - in shorts, blazers, and occasionally suspenders (St Trinian’s, I’m looking at you).

Whether it’s Darrell Rivers battling her short temper or Lord Mauleverer (often described as being too “lazy to live”, drifting through life on inherited boredom, these stories weren’t just bedtime fare. They were manuals. They told you how to behave, who to become, and what fate awaited the bully, the swot, or the dreamy misfit who liked poetry more than rugby.

The school story is Britain’s most persistent fiction - not because we all went to boarding school, but because it taught us to believe we had.

Now - eyes front, backs straight, and bring your own jam tart - I shall explain the syllabus.

Plotting the Timetable, Seven Stories in a School Uniform

Long before Hogwarts got its timetable, school and boarding school stories had theirs. Not just Latin on Tuesdays and Detention on Thursdays, but the deeper kind of timetable, the unwritten plots that march every school story along like prefects on a power trip.

That’s right, just seven. And every school story you’ve ever read is basically in fancy dress as one (or several) of them. Let's ring the bell and see what’s on the lesson plan.

Overcoming the Monster

Think: bullies, tyrants, sinister school staff, or a nasty bit of internalised self-loathing. The monster isn’t always Grendel; sometimes it’s your Latin master.

Tom Brown’s Schooldays gave us Flashman, the worst-bully of Victorian fiction. Sadistic, snobbish, and ultimately disgraced. The real victory? Not just surviving, but surviving with principles intact.

In The Tulip Touch, Anne Fine’s psychological boarding-school-adjacent thriller, the "monster" is a manipulative friendship that turns feral. Tulip isn’t a vampire, she’s worse. She’s charismatic.

Harry Potter throws in Voldemort, Snape, and Malfoy, just to be safe. It’s Overcoming the Monster on a mega-franchise budget.

Rags to Riches

Or, in Enid Blyton’s world, "gypsy girl" to head girl. It’s class mobility on toast.

The School at the Chalet (Elinor M. Brent-Dyer) kicks off with Joey Bettany, whose life is one long swoop upward, from sickly sibling to international darling of the Tyrol.

Goodnight Mister Tom doesn’t strictly sit on the dormitory bedpost, but its evacuee narrative mimics this arc: William Beech moves from neglected child to empowered student.

Even Billy Bunter flirts with this plot, if only Bunter could ever get rich (or thin) enough to stay there. He dreams of jam tarts; the reader dreams of his transformation.

Neither gets what they want.

The Quest

Every term is a quest: survive exams, find your blazer, recover from that midnight feast.

Malory Towers often seen as bunfight comedy, but it’s secretly a search for maturity. Every book is a moral obstacle course, with Darrell Rivers doing battle with her temper and other girls’ egos.

The Dark is Rising isn’t a school book, but Will Stanton is a schoolboy, so we’ll count it. His quest pits light against dark, complete with Arthurian overtones. If Hogwarts had more existential dread, it might look like this.

The Mystery of the Burnt Cottage (yes, Enid Blyton again) has the Famous Five-ish Find-Outers solving puzzles while juggling holidays and ice buns. It’s Quest lite, with lashings of ginger beer and postwar optimism.

Voyage and Return

This one’s almost tailor-made for the boarding school story. You arrive, you adapt, you go home changed, or scarred or scarred and changed. Either way, you return.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: Four children evacuated from the Blitz go to a professor’s house, fall through a wardrobe, and return changed forever. It’s a public school education with added fauns.

Peter Pan is really an Edwardian schoolboy fantasy of escape and delayed adulthood. The voyage? To Neverland. The return? To a nursery that looks suspiciously like a prep school.

In Treasure Island, Jim Hawkins leaves the inn, finds a map, endures pirates, and comes back older, wiser, and with just enough PTSD to justify the genre.

Comedy

Comedy in school stories is all about pranks, misunderstandings, and adults behaving like children.

Jennings and Darbishire by Anthony Buckeridge: The Latin teacher is a pompous windbag, the school rules are an obstacle course, and the boys are plotting endless mischief that never quite lands how they planned.

Madame Doubtfire (Anne Fine again, what a range!) isn’t set in a school, but its dialogue and emotional arc show the same pattern: chaos > misunderstanding > catharsis. There’s a reason Robin Williams ran with it.

St. Trinian’s is the full smorgasbord. The plot barely matters. The girls run riot; the teachers hide in broom cupboards; society collapses to the sound of cackling sixth-formers in suspenders.

Tragedy

Rare, but devastating. When school stories go dark, they go very dark.

Lord of the Flies is the ultimate boarding school breakdown. No blazers, no bell. Just hierarchy, murder, and a dead parachutist in a tree.

Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman drags Romeo and Juliet into racial apartheid. The school? Segregated. The tragedy? Preordained. Booker’s five-stage arc plays out in brutal slow motion.

The Tulip Touch again deserves a place on the shelf here. The breakdown of childhood friendship is the emotional equivalent of a slow-burning house fire.

Rebirth

The child changes. The world doesn’t. But perhaps the reader does.

Marianne Dreams (Catherine Storr): a sick girl dreams herself into a magical world drawn in pencil. Redemption comes not through adventure, but through imagination as healing.

A Little Princess (Frances Hodgson Burnett) goes full Dickens-meets-fairy-tale. Sara Crewe suffers nobly, loses everything, and is reborn in velvet and diamonds. The fantasy of moral superiority rewarded.

The Secret Garden is practically a how-to guide on Edwardian spiritual rebirth: fresh air, good company, and the correct moral outlook and nature can heal anything, even colonial guilt and spinal injury. Deeply problematic in it's representation of India and Indians.

Not Just Plot: The Boarding School as Character Factory

The best plots don’t just tick structural boxes, they create characters we root for or revile. In school fiction, that usually means:

The fiery rebel (Darrell Rivers)

The swot (Elizabeth Allen)

The mean girl (Gwendoline Lacey)

The misunderstood loner (Miss Grayling, we see you)

Names matter. Blyton loves a gender-bending nickname: Clem, Tim, Dickie. These aren’t just schoolgirl shorthand, they’re miniature acts of rebellion in pleated skirts.

Descriptions are quick and iconic:

“He was very tall, and thin as a young birch tree.” Alan Garner's The Moon of Gomrath published in 1969.

You don’t need five pages of backstory when a white beard and a wind-blown cloak will do.

Dialogue, Dialect, and the Right Kind of Silence

Writers like David Almond (Kit’s Wilderness) know that a child’s voice isn’t just the arrangement of words and phrases, it’s rhythm, humour, awkwardness. It’s:

“Nowt,” I spat. “Bloody nowt.”

That’s more authentic than any number of inner monologues.

Good dialogue is plot. It reveals, hides, masks, exposes. The best school stories use it like a weapon - between peers, or across the staffroom battlements.

The Author’s Cloak: Ideology in a Blazer

Whether they like it or not, most authors smuggle in values - class, gender roles, empire, obedience - sewn into the school badge.

Angela Brazil and Antonia Forest didn’t set out to write sociological manifestos. But they did. Their books are dripping in early 20th-century ideology, from chapel to lacrosse pitch.

Jill Paton Walsh argued that writers shouldn’t be preachers.

A novel is written only when the process is set free from the author’s fixed ideas.

But even she knew there’s no such thing as a value-free sentence in a school novel. A tuck box can be political. In a world where the 'haves' and 'have-nots' were often sharply divided, what went into a tuck box and how it was treated became a quiet but potent commentary on class structures. Who had the best tuck boxes, who shared (or didn't), and who got the hand-me-downs could reflect underlying attitudes about wealth, status, and personal worth. In this way, the seemingly innocent object becomes a subtle reinforcement of the class dynamics that ran through the 20th-century school books.

Final Bell: Plot is Just the Beginning

Every school story is a performance: part morality play, part Greek drama, part Edwardian daydream. The seven plots are just the syllabus. What matters is how they’re taught, and who gets detention.

Whether the child overcomes a monster, or simply survives maths, school stories continue to work because they speak to a reader’s deep fear: "Will I make it through?" And their deeper hope: "Will I be changed for the better?"

In that sense, every school story is about graduation - not just from one year to the next, but from who you were to who you might become.

David Salariya has spent far too long in the queue for the tuck shop, peering into the world of school stories - ludicrous tales of blazers, bullies, and ever-elusive jam tarts. A publisher writer and illustrator, David’s spent his career unpicking the seven plots that every boarding school book ever follows. When he's not rifling through the classics, he contributes unsolicited wisdom to The Bookseller and championing the cause that everyone involved in creating a book - right down to the person who found the right shade of green for the cover-deserves to be credited. With an eye for the absurd and a knack for spotting the moral in all that mischief, David is here to prove that school stories are as much about shaping minds as they are about pranks and pithy catchphrases.

Because let’s face it, we’re all just waiting for that jammy tart to arrive.

More ramblings at www.davidsalariya.com

Dan Dare was a British science fiction comic strip character, created by artist Frank Hampson in 1950 for the Eagle comic. He was the hero in stories set in a future where he was a space pilot and adventurer. Known for his distinctive look: pilot’s uniform, a square jaw, and a no-nonsense attitude, Dan Dare was the Buzz Light Year of the 1950s with more brylcream. The comic strip,mixed high adventure, futuristic technology, and bold storytelling, hugely popular in post-war Britain and was a symbol of optimism and exploration during a time of rebuilding. His battles against villains like the Mekon, a green-skinned alien, and other space threats were not just exciting but also often had underlying moral and philosophical themes. Dan Dare captured the imagination of young readers and embodied the sense of a bright future through space exploration.

Comments